We are in the midst of a culinary orgie, thanks, in part, to the Food Network, Top Chef, Nora Ephron, and Julie Powell. Even the New York Times got into the act, running pieces by both Michael Pollan and Maureen Dowd. Pollan’s article starts off as more reflective. He recalls watching Julia Child on TV and how it changed the cuisine in his childhood home (for the better) and the types of dishes his mother would make thanks to JC’s show.

Pollan’s piece got me thinking about my own food memories. Julia Child was not a figure that loomed large in the culinary landscape of my childhood. I remember catching bits of her show on PBS and thinking she sounded a lot like the Chef from the Muppets, but apart from that I can’t say she had any sort of impact on me, let alone on my mother or even my grandmother’s cooking. The women [and man] in my family have had a love/hate relationship with cooking that can be traced back mainly on the maternal side of the family, starting with my grandmother.

In the 1970’s, my grandmother owned an Italian restaurant in a little town in upstate New York (now, it’s a fashionable “weekend getaway” neighborhood, back then it was a hick town). She was the only [Italian] restaurant in the area, and the place was a family affair with my grandfather hosting and running the front of the house, my mom waitressing and my dad helping out in the kitchen. My grandmother introduced the neighbors to eggplant, broccoli rabe, homemade ravioli, soft, pillow-like gnocchi, and fresh basil. On Sundays, she sold plates of pasta and meatballs for $1.50 She was living her dream. Then, the first Domino’s Pizza moved in and shortly after, my grandmother’s culinary dream went up in smoke.

My mother, having spent a good part of her childhood and young adulthood cleaning up after my grandmother’s culinary adventures in the kitchen, hated cooking. She grew up eating the freshest food available, grown in small, but lush backyard gardens in the Bronx and cooked by my grandmother and great grandmother, who argued (in Italian) about which olive oil to use for a particular dish (the virgin or the extra virgin). Sunday dinners in that house were an event that all of the relatives would partake in, showing up with Corningware dishes filled with garlicky aromas and the scent of fresh basil or stewed tomatoes. The inevitable bottle of homemade wine would be cracked open and each child would be given a peach pit, drenched in wine, to suck on while the adults drank glasses of wine or demitasse cups of espresso with a slice of lemon.

When my mom grew up, she never cooked. Instead, she married my father, who (as luck would have it) learned to cook from his mother. He and his brothers (my uncles) were required to make dinner as part of their daily chores since both parents worked. My dad, being the youngest, always got stuck with dinner duty. The first (and only) meal my mom tried to cook for my dad involved Salisbury steak, and, due to the absence of oil to coat the pan, my mom thought karo syrup would be an appropriate substitute. Much to her dismay, not only did the sirloin patties have to be thrown out but the pan as well, since the patties were glued to the pan thanks to the karo syrup. That night they ordered out and did so nearly every night until my sister was born.

sirloin patties have to be thrown out but the pan as well, since the patties were glued to the pan thanks to the karo syrup. That night they ordered out and did so nearly every night until my sister was born.

In 1985, my dad was working in the meatpacking district (again, before it was fashionable and when Stella McCartney was a place called “Quality Meats” a fact my dad likes to dwell on when we walk past there today). My father started as a meat inspector for the government, which pretty much entailed him threatening to shut every place down (from what is now La Perla all the way to Diane Furstenberg) that was in violation of the health code, or, conversely, the macho mafia-type meat men threatening to shut my father down with a gun. He then moved on to a safer career, as a meat purveyor to restaurants around New York including the Carnegie Deli and Windows on the World. The irony at this point was that my dad (and the rest of our family) never ate meat.

Long before Gwenyth Paltrow even knew what tempeh was, my family was macrobiotic. My breakfasts consisted of millet and miso soup. My sister snacked on nori (seaweed) and raw kale. When we went to birthday parties, we arrived armed with our own soy pizza (organic, whole wheat crust, tomatoes and soy cheese) and something called a magic brownie, (not what you’d think) a chocolate-less, dairy-less, sugar-less,

& flour-less square of carob with walnuts. If we went to a 4th of July BBQ, we brought our own tofu pups (tofu hot dogs) and potato salad made with Nasoyaise (tofu mayonnaise, which I still prefer to this day). My sister and I didn’t eat red meat until we were ages seven and 11, respectively. We had the occasional bit of chicken or fish, but I don’t really remember it. Our grains and veggies were eaten when in season, we never drank with meals (and when we did drink, it was water or a natural black cherry spritzer) and French cooking was the farthest thing away from seared tofu and arugala sandwiches that you could get. I don’t even remember ever having butter in our house (quelle horreur!) After eight years of eating Amy’s soy pizzas, tofu, miso, veggies, and bulgar burgers and whatever food the local health food store cooked up that day, my parents saw that macro was still too micro in the mainstream food world for us to continue to function without them attempting to cook on daily basis. Little by little, skim milk began to replace soy milk, turkey replaced tempeh, and cheese, the chard. I also ate my first hot dog (and promptly threw it up). Things only got worse from there.

Take out menus replaced the Moosewood cook book and candy suddenly appeared — the first time my parents gave my sister a chocolate bunny for Easter, she played with it, not knowing it was edible. Our waistlines also grew and so did the battle to keep them down without having to resort back to the granola crunching lifestyle. Cooking a meal was only something we did when company came. Any other time, we went out to eat or ordered take out. We had a tab at the local Italian restaurant. When I went off to college (ironically situated in the same town as the famed Moosewood restaurant) I thought such things were normal, only to discover in my first month away that people would reminisce about what foods their parents (mainly their moms) cooked. “Her tuna casserole,” “My dad’s fish tacos,” “My mother’s steak and pomme frites.” They turned to me. “My mom’s take out menus,” I said, only half kidding.

My junior year of college, my roommate with an aspiring Stepford wife. She made everything from scratch. One day she told me she was going to make a chocolate cake. “But we don’t have cake mix,” I informed her. She looked at me like I was crazy. “I don’t need cake mix,” she said. I quietly wondered just how she was going to accomplish this without a mix. It never occurred to me that one could make a cake with flour, sugar, milk and eggs. I (sheepishly) watched her measure, pour, whisk, bake and create. All she had to do was follow the recipe and liquids became solids (and vise versa). It felt a bit like watching a magician perform an illusion that you know has a logical answer, but you just can’t wrap your mind around it.

During my senior year of college, I discovered the Style Network and their one cooking show, and import from the BBC, Nigella Bites. A dark-haired, British woman who clearly loved to eat (as illustrated by her curvy figure) and with a penchant for chocolate, Nigella Lawson taught me that preparing food is a form of entertainment and almost as fun as, well, sex. The camera work was borderline pornographic, with shots of Lawson sucking up oil-soaked spaghetti, naked chickens being rubbed down with butter, the pop and sizzle sounds of a ham as it developed its brown sugar crackling. But most impressive to me was the chopping. Nigella’s Global knife glinted and flashed as she quickly diced an onion (”it need not be cut perfectly,” she would say), chopped carrots or deboned a duck. Until then, I never realized that the act of cooking itself could be so full of pleasure. A type of creation, but

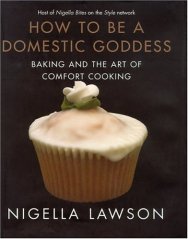

better yet, a creation that can be celebrated and nourish family & friends (as was always exhibited by the merry house-full of guests that Nigella had share the fruits of her labor at the close of an episode). That same day, I purchased my very first cook book, Lawson’s How to Be a Domestic Goddess (Yes, the title is unfortunate, especially if you consider yourself a feminist). At the time, I heard baking was even harder to learn than cooking savory dishes because of the accuracy you need with ingredients and chemistry (I now know this to be half true). I knew introducing myself to the harder of the two would make anything else seem like … a cakewalk.

I proved to be a natural baker from charlottes to pavlovas, biscottis to pies. It’s all about measuring, following directions and maintaining as much control over your environment (temperature, humidity, sound, work space, etc) as possible. Around the same time, I stumbled onto Julie Powell’s blog. Julie was way more of a cook than I was when she started the Julie/Julia Project, but I thoroughly enjoyed following her exploits, tortures and cheering on her successes. Both Julie Powell and Julia Child’s fearlessness encouraged me to branch out from the Brits (at this point, I had also included Jamie Oliver, Rose Gray and Ruth Rogers into my culinary fold) and turn to the Italians (with The Silver Spoon cook book), the food scientists (with Hervé This and Molecular Gastronomy) and even back to my old organic roots and on American soil (with Alice Waters). I read cook books like they were novels, until I realized there was a whole genre of books about food and cooking like The Omnivore’s Dilemma and Animal, Vegetable, Miracle.

In 2004, however, I caught the Julia Child fever when My Life in France was published. I read about Child’s life even before I tried any of her recipes. I got caught up in her spirit, her humor and the voice –which by now I was googling online for video clips just so I could hear it. One of the most defining quotes from My Life in France is actually attributed to Paul Child, Julia’s husband: “If variety is the spice of life, my life must be one of the spiciest you ever heard of. A curry of a life.” It is the Childs’ zest for life and how they embrace the journey, even the unknown, that made me approach my own “unknown” challenges with more enjoyment and less fear.

I only recently started cooking from Mastering the Art of French Cooking vol. 1, when a copy of the book was given to me

at the Julie & Julia set sale (it was one of five used in the film). I perused the book, afraid the Julia Child I had gotten to know through My Life in France and her biography wouldn’t be as evident in cook book speak. But, I began to finding familiar phrases and Julia’s same authoritative, exacting voice, still with that hint of humor and mischief. Ah, there was the Julia I knew. The first recipe I tried was simple. The name, cherry clafoutis, caught my eye because it happened to be the start of cherry season. The resulting clafoutis was sweet, but slightly tart, and a little custardy. Like a more dense version of a crepe. It was delicious.

at the Julie & Julia set sale (it was one of five used in the film). I perused the book, afraid the Julia Child I had gotten to know through My Life in France and her biography wouldn’t be as evident in cook book speak. But, I began to finding familiar phrases and Julia’s same authoritative, exacting voice, still with that hint of humor and mischief. Ah, there was the Julia I knew. The first recipe I tried was simple. The name, cherry clafoutis, caught my eye because it happened to be the start of cherry season. The resulting clafoutis was sweet, but slightly tart, and a little custardy. Like a more dense version of a crepe. It was delicious.

I might not yet be ready to master Julia’s omelette or French bread recipes, but my culinary mentors have taught me to embrace cooking and food in a way I never witnessed growing up: with conviction, love, joy, and absolute fearlessness.